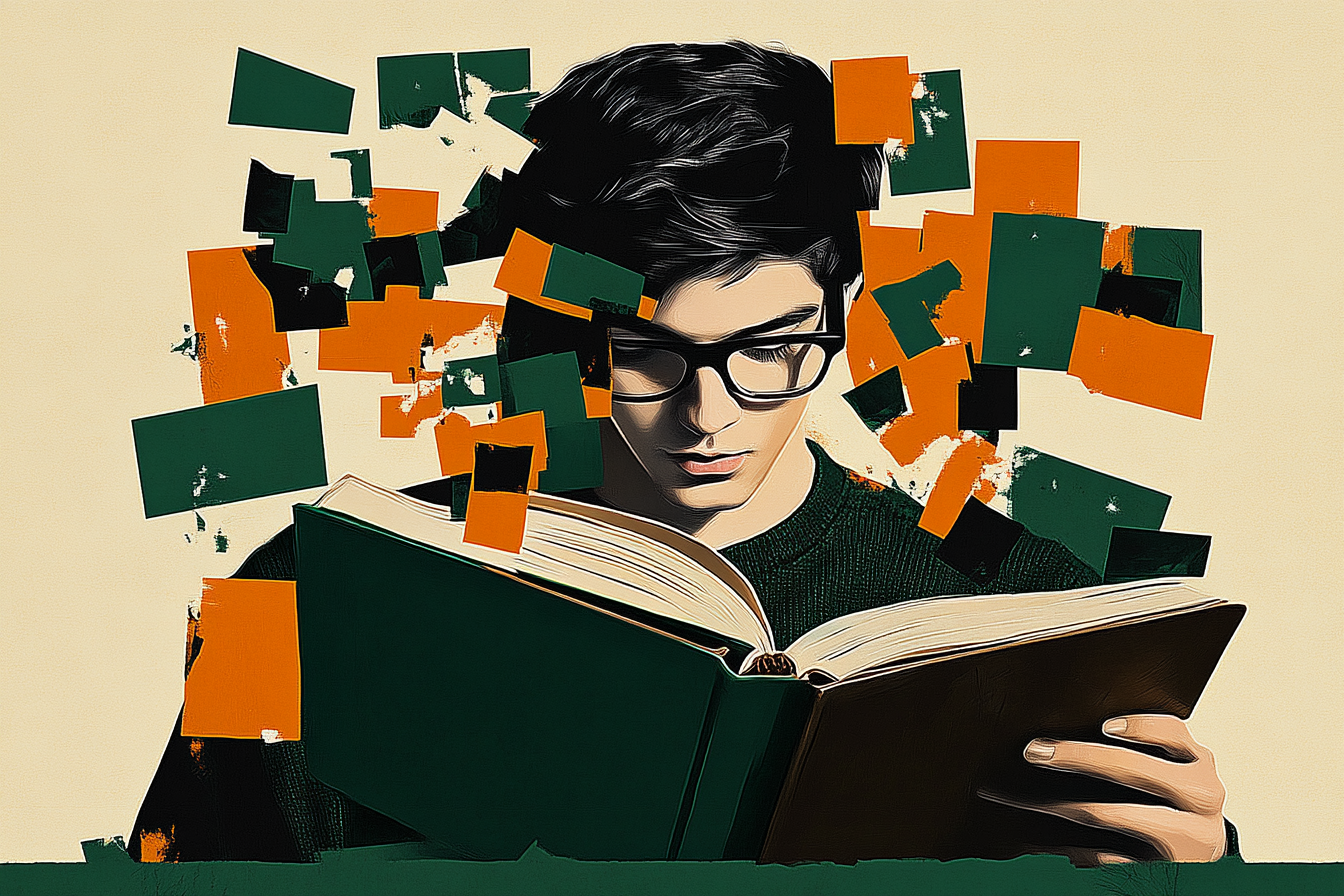

Innovation is synthesis of what we already have, but moving up against entropy barriers of scale and complexity.

The Reactants Are Already on the Shelf

Economist Brian Arthur argued in The Nature of Technology (2009) that "novel technologies arise by combination of existing technologies." Not from blank-slate genius. Not from lightning bolts of inspiration. From synthesis.

Think of innovation like chemistry. New compounds emerge from combining elements already present on the laboratory shelves. The breakthrough isn't creating new atoms—it's understanding which ones, mixed in what proportions under what conditions, produce something useful.

A piece of smart home electronics? It's WiFi and Bluetooth, FR4 circuit boards and plastics, microcontrollers and graphical user interfaces. Each component was innovated well before anyone conceived of smart homes. The innovation is in the recombination.

The diesel engine emerged from physics principles and practical tinkering—Rudolf Diesel filed his patent in 1893, building on Carnot's thermodynamic theory from 1824. Wheels on suitcases were patented as early as the 1920s and 1940s, but only became universal when adjacent markets evolved: larger airports, more passenger flights, and the decline of porters. The innovation wasn't the invention. It was the synthesis at the right time with the right complementary pieces.

The Entropy Problem

Here's where it gets interesting and difficult.

If the inputs to contemporary innovation have become plentiful—and they have—then innovating becomes an effort working against high entropy barriers.

The vast number of options becomes friction. There are limits to what can be known and tried. You're not constrained by lack of building blocks. You're constrained by the inability to survey them all, understand their properties, and test combinations fast enough.

This is the innovator's paradox: abundance creates its own scarcity. When everything is possible, knowing what exists and what it does becomes the bottleneck.

Knowledge as Infrastructure

If innovation is synthesis, then knowledge of available parts, their attributes, and costs becomes a major factor. Not just technical specifications. Understanding that such parts exist in the first place is itself effort.

A chemist needs to know what's in the lab cabinet. A software developer needs to know what APIs are available. A product designer needs to know what materials and manufacturing processes exist. A business strategist needs to know what technologies, platforms, and data sources can be connected.

The innovative character of a creation emerges from the interplay of parts and the degrees of freedom their recombination permits. But you can't recombine what you don't know about.

Layers Upon Layers

Once knowledge itself is understood as part of innovation, better means to acquire such knowledge becomes itself an innovation. A layered system takes form.

This is why search engines were transformative. Why GitHub changed software development. Why platforms that connect previously siloed capabilities unlock new possibilities.

Knowledge infrastructure doesn't just accelerate existing innovation—it enables entirely new categories. Previously unknown combinations become discoverable at scale, and by people who don't bring decades of specialized education to the table. The assumptions and path dependencies of established experts become less binding when newcomers can survey the landscape directly.

The Human Element Remains

But let's not abstract this into pure economics.

Individual courage, grit, and obsession bring about specific innovations. Rudolf Diesel pursued his engine partly in service of a socialist utopia—he believed small-scale, efficient power would free craftsmen from dependence on large factories. That vision never came to pass, but the engine did. The weird and countercultural beginnings of the software revolution saw mind-altering psychedelics and computers linked by early innovators like Stewart Brand, who moved fluidly between Ken Kesey's acid tests and Doug Engelbart's Augmentation Research Center.

Wide-ranging oddball beliefs appear overrepresented among innovators. The synthesis model doesn't erase the need for human vision—it amplifies it. Knowing your ingredients doesn't tell you what to cook. That's where creativity, even weirdness, remains essential.

The same components can be synthesized a thousand ways. Knowledge gives you possibility. Creativity gives you direction.

Working Against Entropy

In the trenches of innovation—especially in startup settings—the things that can be synthesized are a source of joy and hope. The inputs are plentiful.

But regulations, diverse global markets, and the sheer complexity of options add entropy barriers and costs. Complementary markets have emerged to trade in support functions: accelerators, consultancies, platforms, tools to help navigate the possibility space.

The work of productive innovation in our time is surveying what exists, understanding properties and mechanics, identifying high-potential combinations, testing rapidly against reality, and iterating through the friction. It's methodical. It's combinatorial. It requires tolerance for discomfort at both individual and organizational levels.

The Path Forward

We live in a time of remarkable abundance. The shelves, figurative and literal, are overflowing.

The limiting factor isn't access to components. It's navigating it all effectively. Knowing what building blocks exist. Understanding their properties and constraints. Having systems to identify promising combinations. Maintaining the creativity and courage to try unusual syntheses.

The entropy is high. The maps are incomplete.

Further Reading

- Brian Arthur, The Nature of Technology: What It Is and How It Evolves (2009)

- Matt Ridley, How Innovation Works: And Why It Flourishes in Freedom (2020)

- Steven Johnson, Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation (2010)